“We Are Witnesses” is a new series of short videos produced by The Marshall Project and The New Yorker, offering incredibly powerful testimony from 20 people whose lives have become enmeshed in the U.S. criminal system.

“We Are Witnesses” is a new series of short videos produced by The Marshall Project and The New Yorker, offering incredibly powerful testimony from 20 people whose lives have become enmeshed in the U.S. criminal system.

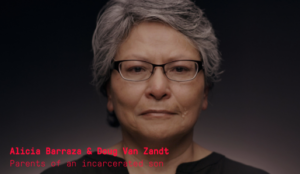

Two of the videos feature CAIC members. One is about Alicia Barraza and Doug Van Zandt, whose son Ben committed suicide in solitary. One is about Tyrrell Muhammad, who was in prison for 26 years and 11 months, including 7 years in solitary.

“You don’t even know when you lose your mind.” Tyrrell Muhammad describes the experience of solitary confinement: “Usually when we have a snowstorm, after 3 days we get cabin fever, everybody wants to get out. Solitary confinement? There’s no getting out.” He talks about how solitary caused him to start to lose his hold on reality, seeing “figurines” in the paint patterns on the wall of his cell that “look like Abraham Lincoln.”

“Then you’re saying to yourself, ‘That’s not Abraham Lincoln. Stop it. Cut it out,’” he says. “You’re battling yourself for your sanity. And it’s a hell of a battle.”

“He wasn’t a bad kid. He was just a kid that was mentally ill.” Alicia Barraza and Doug Van Zandt talk about their son Ben, who despite being 17 years old and diagnosed with a mental illness, was not granted youthful offender status by the DA.

“He wasn’t a bad kid. He was just a kid that was mentally ill.” Alicia Barraza and Doug Van Zandt talk about their son Ben, who despite being 17 years old and diagnosed with a mental illness, was not granted youthful offender status by the DA.

“I wanted to help him, and protect him, but then at the same time, he was already in this criminal system,” Alicia says. “He left us a note. He just said, ‘Please tell my family I love them.’”

Please watch and share!

https://www.themarshallproject.org/witnesses?share=tyrrell

https://www.themarshallproject.org/witnesses?share=alicia-doug

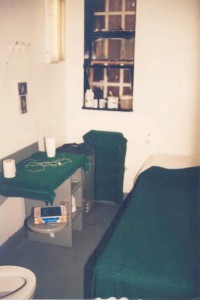

William Blake is in solitary confinement at Elmira Correctional Facility in upstate New York. In 1987, while in county court on a drug charge, Blake, then 23, grabbed a gun from a sheriff’s deputy and, in a failed escape attempt, murdered one deputy and wounded another. He is now 50 years old, and is serving a sentence of 77 years to life. Blake is one of the few people in New York to be held in “administrative” rather than “disciplinary” segregation—meaning he’s considered a risk to prison safety and is in isolation more or less indefinitely, despite periodic pro forma reviews of his status. He is now in his 27th year of solitary confinement.

William Blake is in solitary confinement at Elmira Correctional Facility in upstate New York. In 1987, while in county court on a drug charge, Blake, then 23, grabbed a gun from a sheriff’s deputy and, in a failed escape attempt, murdered one deputy and wounded another. He is now 50 years old, and is serving a sentence of 77 years to life. Blake is one of the few people in New York to be held in “administrative” rather than “disciplinary” segregation—meaning he’s considered a risk to prison safety and is in isolation more or less indefinitely, despite periodic pro forma reviews of his status. He is now in his 27th year of solitary confinement.

Follow the #HALTsolitary Campaign