Reprinted from Solitary Watch.

The following post is a chapter from an unpublished book by Mary Buser, who worked in various capacities in the mental health system on Rikers Island. In Buser’s own words: “I worked in the Rikers Mental Health Department as a psychiatric social worker for five and a half years, leaving Rikers in 2000. I started off as a student intern in the island’s sole women’s jail…[and] returned to Rikers to work in a maximum security men’s jail…[then] was promoted to assistant chief of Mental Health in another jail, where I supervised treatment to the island’s most severely mentally ill inmates. From there, I was transferred to my fourth and final jail, which was connected to the “Central Punitive Segregation Unit,” aka, the Bing. Here, I supervised a mental health team in treating inmates held in solitary confinement–determining whether or not someone warranted a temporary reprieve based on the likelihood of a completed suicide. Although I had become disillusioned with the criminal justice system, the Bing was my Rikers undoing. The final section of my manuscript is focused on my daily trips to the Bing, the inmates who occupied these cells, and my struggle to justify doing this work.” Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved in the episodes Buser describes.

As jails have come to replace psychiatric hospitals as repositories for people with mental illness, Rikers become one of the nation’s largest inpatient mental health centers (second only to the L.A. County Jail). A disproportionate number of these psychiatrically disabled individuals end up in solitary confinement, doing “Bing time” for rule infractions precipitated by their illness. Buser’s account of her time overseeing treatment in “the Bing” is of particular interest now, when years of activism by the Jails Action Coalition and two scathing reports commissioned by the New York City Board of Correction have finally spurred efforts to reduce the use of solitary and improve mental health treatment on Rikers. These efforts have thusfar yielded at best mixed results. –James Ridgeway

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

At the end of a long cinderblock corridor, a guard in an elevated booth passes the time with a paperback book. Across from the booth, a barred gate cordons off a dim passageway. Along the passageway wall are the words: CENTRAL PUNITIVE SEGREGATION UNIT.

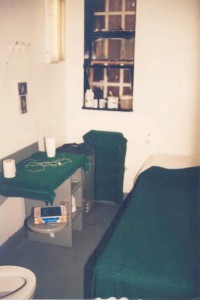

The guard looks up as I approach, and nods. As acting chief of “Mental Health,” I’m a regular over here at the “Bing” – an unlikely nickname for this five-story tower of nothing but solitary cells — 100 of them on each floor. Designed for Rikers Island’s most recalcitrant inmates, the occupants of these cells have been pulled out of general population for fighting, weapons possession, disobeying orders, assault on staff. The guards refer to them as “the baddest of the bad” – “the worst of the worst.” I’m not so sure about that.

The guard throws a switch and the barred gate shudders and starts opening. Around a bend, I step into an elevator car. Since the problem inmate is on the third floor, I hold up three fingers to a corner camera, waiting to be spotted on a TV monitor. This is no ordinary elevator — no buttons to push here, likely engineered for some security purpose. The sweaty little box starts lifting, and as the muffled wails of the punished echo through, my stomach tightens — the way it does every time I’m called over here, which is often. Solitary confinement is punishment taken to the extreme, inducing the bleakest of depression, plunging despair, and terrifying hallucinations. The Mental Health Department looms large in a solitary unit – doling out anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, and mountains of sleeping pills. If these inmates had no mental health issues before they entered solitary, they do now. But even the most potent medications reach only so far, and when they can no longer hold a person’s psyche together – when human behavior deteriorates into frantic scenes of self-mutilation and makeshift nooses – we’re called to a cell door.

The elevator rattles open on the third floor. Ahead, a foreboding window separates two plain doors, each one leading onto a 50-cell wing. Behind the window, correctional staff hover over paperwork. A logbook is thrust out, I sign it, and point to the door on the left, ‘3 South.’ When the knob buzzes, I pull the door open and step into what feels like a furnace. A long cement floor is lined with gray steel doors that face each other – twenty-five on one side, twenty-five on the other. Each door has a small window at the top, and on the bottom, a flap for food trays.

At the far end, Dr. Diaz and Pete Majors are waiting for me. I hesitate for a moment, dreading the walk through the gauntlet of misery. The smell of vomit and feces hangs in the hot, thick air. Bracing myself, I start past the doors, trying to stay focused on my colleagues. Still, I can see their faces – dark-skinned, young – pressed up against the cell windows, eyes wild with panic. “Miss! Help! Please, Miss!!” They bang and slap the doors, sweaty palms sliding down the windows. “We’re dying in here, Miss – we’re dying!” Resisting my natural instinct to rush to their aid, I keep going, reminding myself that there’s a reason they’re in here – that they’ve done something to warrant this punishment. The guards, themselves sweat-soaked and agitated, amble from cell to cell, pounding the doors with their fists, spinning around and kicking them with boot heels — “SHUT—THE FUCK– UPPP!!”

In the meantime, Pendergrass expects there will be some who feel the current deal goes too far, just as others believe it does not go far enough. He did not specify where the “pushback” is likely to come from. But in the past,

In the meantime, Pendergrass expects there will be some who feel the current deal goes too far, just as others believe it does not go far enough. He did not specify where the “pushback” is likely to come from. But in the past,

Follow the #HALTsolitary Campaign